Low-dose aspirin (LDA) is remarkably effective at preventing preeclampsia, a serious pregnancy complication associated with maternal and infant morbidity and mortality. Experts in obstetrics and gynecology and disease prevention have endorsed LDA usage at 81 mg for years. It’s a safe, high-impact intervention with few side effects that is available over the counter.

And yet, preeclampsia impacts 1 in 14 pregnancies in California today, according to the California Department of Public Health (CDPH). Many pregnant people don’t know the signs and symptoms of preeclampsia and are not prescribed LDA despite being at risk.

The California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative (CMQCC) is partnering with the March of Dimes as well as hospitals, community organizations, and patients statewide to promote the usage of LDA for preeclampsia prevention.

A primary aim of CMQCC’s LDA initiative is ensuring all pregnant people are screened for preeclampsia, ideally during their first prenatal visit. Low-dose aspirin use for those at risk should begin between 12 and 16 weeks gestation, though initiation can occur anytime up to 28 weeks.

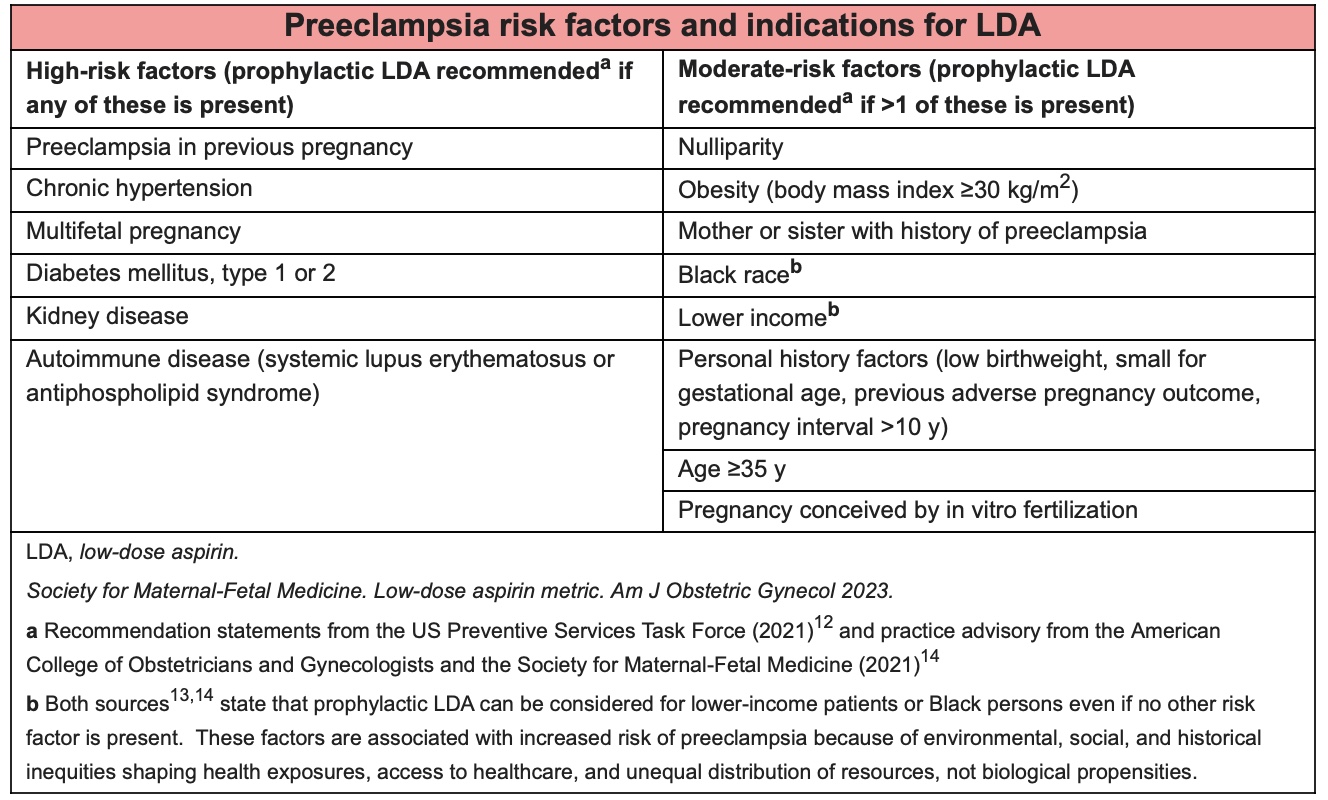

In 2021, U.S. Preventative Services Task Force (USPSTF), American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM) issued a joint recommendation for daily prenatal LDA for pregnant people with any high-risk preeclampsia factor, or 2 or more moderate risk factors. While high risk factors are generally related to preexisting health conditions like chronic hypertension or diabetes, moderate risk factors are more closely associated with demographic characteristics and include age ³ 35 years, obesity (body mass index ³ 30), Black race (as a proxy for racism), and lower income.

Medical Lead with the LDA initiative and Clinical Innovation Advisor for CMQCC, Amanda Williams, MD, MPH, recognizes these conversations around risk may be uncomfortable for clinicians, especially when meeting a patient for the first time.

“It’s really important to use non-blaming language, or anything that could seem like being at risk is their fault, or they did something wrong,” says Dr. Williams, who has trained many residents on prenatal counseling. Her recommendations to physicians are informed by her own personal experience, as she had preterm pre-eclampsia with severe features and a baby in the NICU.

“When you tell someone: ‘you’re overweight,’ ‘you’re Black,’ ‘you’re poor,’ without any further explanation, that doesn’t help a patient understand why you’re prescribing LDA,” she says. “This is especially true if it’s a patient who you don’t have a relationship with, or you don’t have cultural concordance with.”

To build trust with patients, Audra Meadows, MD, MPH, Professor of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Sciences at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD), begins by congratulating expectant parents and defining shared goals. Often, she has found, broad goals in the perinatal care space are universal: healthy mom, healthy newborn, term delivery, and a respectful birth experience.

“Having clinical tools to address and prevent preterm birth, tools that are available and offered equitably, is essential to achieving these goals,” Dr. Meadows says. She serves as Professor and Vice Chair for Culture and Justice at UCSD, and is part of a multidisciplinary team at the University who is partnering with CMQCC in the pilot phase of the LDA initiative.

Joining the pilot prompted USCD to make sure information on LDA was available to all communities they serve, especially since they are a tertiary care university system with a large immigrant population. Reviewing their patient data, they identified the top 5 languages spoken by patients and translated written materials.

“With the fact that higher rates of preterm birth and preeclampsia are seen among U.S. born Black women, and with higher rates of maternal morbidity among Black women in the U.S, it’s important to me to make sure as we’re embarking on different initiatives that from the outset we’re taking an equity lens,” says Dr. Meadows, who calls herself a birth optimizer.

When she counsels a patient on preeclampsia prevention, she is careful to choose language that is both specific to what the patient’s goals are and their risk condition(s) based on their health history. She finds conversations about race can be particularly challenging, and also, she sees them as an opportunity to deepen discussions around a shared prenatal care plan and why she’s recommending LDA or other interventions.

The USPSTF, ACOG, and SMFM clearly state that both lower income and Black race are independent risk factors for preeclampsia that reflect “environmental, social, and historical inequities shaping health exposures, access to healthcare, and uneven distribution of resources, not biological propensities” (see graphic). Dr. Meadows reinforces this message with her Black patients, saying it’s the toxic stress of racism, not an inherent difference about their biology, that increases their risk of developing preeclampsia and other disorders of pregnancy. Though she recognizes the necessity of screening for preeclampsia based on demographic data and health history, she looks forward to a time when science will provide more answers about how preeclampsia develops, earlier detection of the disorder, and absolute prevention.

California maternal mortality data released by CDPH this month show that racial-ethnic disparities in maternal deaths decreased in the last measured period of 2018-2020 compared to 2015-2017. Still, rates of death among Black pregnant people were 3.1-3.6 times higher than the rates for Asian, Hispanic/Latino, and White pregnant people.

Eliminating entrenched inequities is central to the mission of the LDA initiative. The CMQCC team is working with California clinicians to help them operationalize screening, providing written materials and videos (coming soon!) simulating these challenging conversations around risk.

Both Drs. Williams and Meadows agree that when counseling patients, providers can start by prioritizing listening over talking.

“We all must listen with our hearts and minds and remember that the more different someone is from us, the harder we need to listen,” Dr. Williams says.

Expert Contributors:

Amanda Williams, MD, MPH, FACOG, is the Clinical Innovation Advisor to the California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative (CMQCC) and serves as an adjunct faculty member in the OBGYN Department at Stanford Medicine. She also is the Medical Director of Mahmee, a pregnancy and postpartum wraparound services company aimed at eliminating maternal health disparities and empowering all patients. Prior to joining Mahmee, Dr. Williams worked at Kaiser Permanente Oakland Medical Center where she served as Director of Maternity Services and also oversaw maternity services for the Kaiser Permanente Northern California region. She has also served on several state and national committees, such as the California Pregnancy-Associated Mortality Review committee and the National Quality Forum Maternal Morbidity and Mortality work group.

Audra Robertson Meadows, MD, MPH, FACOG, is a Professor and Vice Chair for Culture and Justice in the Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Sciences and Course Director for Equity and Systems Science at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine. Dr. Meadows is a birth optimizer – innovating prenatal care, promoting teaming in maternity care, and developing tools that improve obstetric safety and achieve equity. She is a founding director of the state perinatal quality collaborative in MA, PNQIN MA, and currently leads the MA AIM Initiative and Maternal Equity Bundle.

Written by:

Laura Hedli is a science writer for the Division of Neonatal and Developmental Medicine at Stanford University School of Medicine. Her writing has appeared in The Philadelphia Inquirer, The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, American Theatre magazine, Playbill.com, and other print and digital publications. You can reach her at lhedli@stanford.edu.